Paul Crist

Career Biography

● I was born in Atlanta, Georgia on October 3, 1944, while my dad was away at war in the Philippines. Upon his return a year later, we relocated to California.

● After moving several times, the family bought a home and settled in Anaheim, California in 1950. I attended school locally up through junior college and in 1964 went away to Berkeley to finish undergraduate work. I earned money for college during the summer by working as a pastel portrait artist at Disneyland.

● I graduated from UC Berkeley in March, 1967 with a BA in Fine Arts and a minor in Engineering.

● After graduating, I returned to Southern California and worked in the civil engineering field until 1972.

● Tangible interest in stained glass began in college, when I made some projects for a sculpture class, that were constructed out of small pieces of colored Plexiglas, glued together to form shapes that looked suspiciously like Tiffany-style lamp shades.

My First Leaded Shade- 1968

● After returning to Anaheim, I enrolled in a real stained glass class at a local hobby shop in the fall of 1967. The class was taught by a designer from Hollander Glass, who were just beginning to establish themselves as a distributor of stained glass supplies. My first project was a 20” panel lamp shade of my own design. It was a floral motif spread across 10 flat lead-camed panels, carefully joined together to form a geodesic hemisphere. It was the first and last lamp shade I ever made with lead came. A year after finishing my class at the hobby shop, I returned to teach the class for two years and continued to teach stained glass in Adult Education for another three years.

My First Copper-foiled Shade- 1970

made largely from old window glass

An Early Clematis Design- 1974

copied from an old lamp

● For the first three or four years, I worked at home during my free time, honing my skills at making lamps using the copper-foil technique. I made up my own designs for my first shades, but after buying a couple of books on Tiffany, I concluded that his designs were better than my own and began copying them.

● 1968 to 1972 were the early years of the stained glass renaissance and the specialized supplies needed to make copper-foiled lamp shades were not yet available. I had my first two molds turned out of wood, but they were expensive to have made and cumbersome to work with. I soon started making my own molds, in a lighter version out of polyurethane foam, turned on a lathe, sealed with plaster and then covered with fiberglas. Adhesive-backed copper foil tape was not available until 1974, so I had to make my own by at first coating raw copper foil with a mixture of beeswax and Venice Turpentine. This formula, which Gary Hollander told me came from Tiffany Studios, was also painted on the mold to make the glass adhere during assembly. Finding glass suitable for leaded shades was a problem at the time. The only manufacturers of any consequence were Kokomo and Wissmach and I thought their quality didn’t measure up to the glass I was seeing in old windows. Fortunately for me, Victorian stained glass windows had become popular right along with Tiffany, and one local antique wholesaler was bringing in truck loads of them from the East. Some of these windows were damaged beyond repair and I was able to make a deal with the dealer to buy them for as little as $1.00 per sq. ft.! I still have vivid memories of the hours spent in the dusty, smelly and overall odious task of tearing old windows apart to salvage the glass.

An Early Original Design- 1973

on a Mosaic Shade Co. base

● Contact with the local antique dealers also provided me with a source for old lamp bases. In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, very few craftsmen were making leaded glass lamp shades (it was all windows then), so there was almost no market for widowed bases. They were hard to find, but I could usually buy those that turned up for between $15 and $25 apiece. The shade support hardware on these bases was either inappropriate or missing altogether, so I was forced to make it myself. My first choice for reproduction was Handel’s slip cap, because it was a simple one-piece fitter that I could easily have spun. With the publication of Neustadt’s book in 1970, I began to copy the more authentic Tiffany caps and wheels that he showed.

● Around 1970, my skill at crafting authentic-looking lamp shades was good enough that an antique dealer from whom I was buying bases became interested in selling them for me. This came as a surprise, since I made shades because I loved doing it, with no idea that anyone might be interested in actually paying money for my labors. Their motives, on the other had, were probably none too pure and I suspect that my shades were offered to potential customers with an “I’m not sure what it is” sort of sales approach. In any case, I remember consigning my first shade (the dealer provided the base) without much expectation that he would find a buyer for it, and how shocked I was when he called me three days later to tell me that he had $375.00 in cash waiting for me.

● With the revelation that there was a market for my recently acquired skills, I found myself embarked on a new “moonlight” career. The dealers wanted Tiffany designs, so I studied everything I could find on Tiffany and applied what I learned to my work. My relationships with the dealers also gave me the opportunity to inspect old leaded lamp shades, which eventually led to repair work and a greater understanding of the old technology. My reputation for making good shades began to get around and orders increased to the point that I couldn’t keep up with them. In 1971, I rented a small studio in an old office building in Fullerton, where I could spread my stuff out and finally conduct experiments in patination, because I wanted to give my lamp shades a more authentic look. I dubbed my new business the “Glass Workshop,” which was appropriate, because I could usually be found there slaving away on a lamp shade into the wee hours of the morning.

● Needless to say, these long hours soon began to undermine my engineering career. By 1972, I was earning more money making lamps than I was as an engineer, so the decision to turn the Glass Workshop into a full-time career was not a difficult one.

● For the next three years, I worked alone, honing and expanding my skills and building the business. Orders for lamps kept me busy most of the time, but there were a few slow periods when I had to take on more pedestrian work- repairing old windows and even building some new ones. A few of my lamps eventually found their way to the Mid-west where the market for them was better and this got the attention of one of bigger Tiffany dealers (Ted Ingham), who had been fooled by one of my creations. To my disappointment, he had only passing interest in my shades, but was really intrigued by the reproduction Tiffany hardware that I had made to go with them. Many original Tiffany lamps had lost their caps over the years and he had a need for replacement caps and other parts. At the time, my caps and wheels were as much like Tiffany’s as reliance on pictures would permit, which was by no means exact. He offered to supply me with examples of original parts if I would giver him an exclusive and, with that, my Tiffany replacement hardware business was born. To meet the level of quality demanded by the Tiffany dealers, I had to really work on improving my patina. It turned out to be a frustrating experience. Sometimes the parts would look great when they were shipped out, only to be returned a few weeks later with pink spots or a black patina. I had to refinish a lot of parts in those days and it took several years before I was able to turn out a stable and authentic looking patina.

● By 1977, my hardware business was bringing in other Tiffany repair and re-patination, mostly from local collectors and dealers, which provided me with more valuable exposure to original pieces. My Tiffany shade repertoire had grown to more than 20 designs and I had hired two employees to handle the work load. I learned that a couple of my shades had turned up at auction with Tiffany signatures added, so I started signing my work to discourage this fraud and protect my name. Unfortunately, the tags were easy to remove, so in retrospect this measure might have actually abetted the crooks by pointing out exactly where the phony tags should be placed!

● As the quality of my shades improved, it became increasingly clear that my major obstacle was the lack of good glass. My sources for old windows had more or less dried up and the stained glass renaissance was in full stride, so even Kokomo and Wissmach were hard to get. I was lucky enough to have an account with Kokomo and was able to buy a couple of cases with the colors I needed most of the time. I would pick out the best sheets for myself and had a line waiting to buy the rest of it. In 1977, a Tiffany collector/friend of mine named Bob Jordan decided to have a go at reproducing Tiffany’s mottled glass. After consulting with a renowned glass chemist (Dr. Blau), he set up a small one-pot experimental furnace and was soon producing some very convincing Tiffany-like mottled glass. I spent many an evening at Corona Furnaces helping him to do runs and even briefly considered becoming a partner, but it soon became clear that I had neither the time nor dedication needed to be in the glass manufacturing business. I bought or traded a lot of glass of exceptional quality from him, although it was all single-color (he could fire only one pot up at a time), mostly in pastel shades and at $9.50/lb. a definite strain on the budget. Corona’s yellow uranium glass was especially nice and, during the early ‘80s, I turned out dozens of 22” or 28” laburnums based on this gorgeous glass.

● The opalescent glass shortage of the mid and late-‘70s brought several new glass manufacturers onto the scene. Companies like Genesis, Fischer and Orient & Flume made some unique art sheet glass, but none of them kept up this type of production for very long. Bullseye was launched in Portland OR in 1974 and they turned out some very interesting experimental glass while they were developing their product line. I was so hungry for unusual glass at the time that I would spend hours in their warehouse going through boxes of experimental scrap. Unfortunately, this source dried up as they honed in on their repertoire and began to focus more on production to supply the ravenous stained glass market. At one point, I approached Ray Ahlgren (Bullseye’s chemist) about doing some special runs for me, but he regretfully said they were too swamped with orders. He referred me to a local blown glass artist, whom he heard had rolled some custom sheet glass for a local stained glass studio.

● Eric Lovell was more than willing to have a go at making the specialty glass that I was looking for, and thus began a collaboration that would last more than a decade. The birth of Uroboros marked the beginning of a market that has evolved into the many types of art glass available today.

● On the other hand, the early success of Uroboros depended to a large extent on the popularity of Tiffany lamp reproductions. During the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, this market was booming and the handful of manufacturers, like myself, could demand extremely high prices for our creations. Quality art glass was essential to our product and we were willing to pay almost anything for the right stuff. At the $6 to $8 a pound that Uroboros was charging for the specialty glass they made for us, they were able to finance the experimentation that became the foundation of their business.

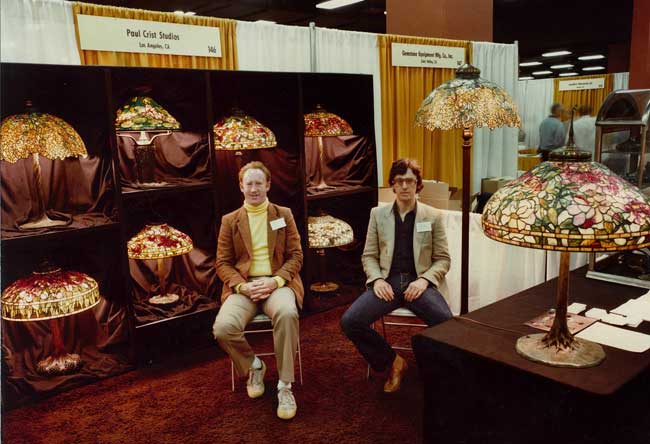

Innaugural PCS Trade Show Exhibition with Russell Friedman and myself – Chicago, 1980

● The continuing demand for my lamp shades led to a period of growth and diversification. At the high point inf 1979-80, I employed 45 craftspersons and turned out an average of 14 shades every month. My shades sold for between $2000. and $5000. apiece and orders had us booked up as far as six months in advance. My repertoire of designs had grown to over 30 different Tiffany models and we were reproducing several of Tiffany’s lamp base designs. This growth and success would have been impossible without the services of two very able and very talented craftspersons; Lynne Johnson, who oversaw the artistic aspects of my shade production and did some very creative designing on the side; and Roger Thomas, who, as my production manager, kept things running as smoothly as could be expected. Roger has gone on to earn his own reputation as an accomplished artist in fused glass.

PCS Soldering Room - ca 1982

● In 1980, I incorporated my business under the name of “Paul Crist Studios.” My reputation for making Tiffany quality shades was becoming more widely known and my name was even being whispered among the general Tiffany trade. This was in part because my shades had begun to show up occasionally in the catalogs of the New York auction houses- usually with Tiffany signatures added- and pictures of a few had been published in Tiffany books as the real thing. During this period, some inquisitive Tiffany dealers showed up at my studio to see what we were doing and learn how not to be fooled. This “negative press” had the positive effect of advertising our expertise and bringing in more work in Tiffany restoration, along with an occasional authentication.

● As an artist, the problem of misrepresentation of my work was a troublesome one. I had suspicions that a few of our big customers were involved in this kind of fraud, but they were a significant part of our business and couldn’t realistically be dropped. During the early ‘80s, Paul Crist Studios made a concerted effort to market our lamps through interior design showrooms and we invested considerable money in consigned inventory and advertising. In the end, this market turned out to be a thin one and we soon realized that it would require more time and money to establish than we could afford. We also introduced several lamps in original designs by Lynne (the Odyssey N221 Spider Mum was one of them), but they were not well received, largely because the market we had cultivated was fixated on Tiffany. A lot of our best business actually came by word-of-mouth through the Tiffany trade. A surprising number of Tiffany collectors were interested in acquiring examples of major Tiffany models that either were not available or they could not afford, or in reproducing a cherished lamp that they had sold, or in simply furnishing a summer cottage with lamps that were not too expensive and also insurable. Whatever their stated reasons, I think that a lot of our legitimate customers also secretly wanted their friends to mistake our lamps for the real thing. Such is human nature.

● The recession of 1982 brought an end to the hot Tiffany reproduction market and we gradually had to pare our staff down until only 6 employees were left. We survived on what little business in high-end reproductions remained, augmented by a small but steady demand for our replacement parts and restoration services. It was during this period that the idea of Odyssey was born. One night over dinner I was complaining to Charlie, an important Tiffany collector, about the dismal state of my business. Charlie’s diagnosis was that what I needed was a “bread and butter” product that was easier to produce and moderately priced, so that it would appeal to a broader market than the one I had locked myself into. Roger provided the other piece of the puzzle when, one day shortly thereafter, he idly mused that other stained glass artists would love to get their hands on our molds and patterns. I began work on my first Odyssey model (the 20” Poppy) in February, 1984 and nine models were ready for sale when I introduced the Odyssey System five months later at the annual stained glass trade show in Baltimore.

● With the end of the recession in 1984, our business in reproductions began to pick up again, although it never would return to the high times of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Fortunately, we now also had our parts and restoration business, which was continuing to develop as awareness of my skills became known and word spread through the industry. Odyssey was also doing well; the system was making a name for itself in the industry and starting to attract the loyal following that would remain its core market up to the present day. The symbiotic relationship between Paul Crist Studios and Odyssey hardly needs mentioning. Beginning with the very first Tiffany shade that I got my hands on in the mid-1970s, I had meticulously documented the best of the originals with photos, measurements, a contour template and a rubbing of the design, in case I wanted to reproduce that particular model later on. By the time Odyssey was introduced in the mid-1980s, I had accumulated 40 or 50 of these documents and they formed the core of what would eventually evolve into more than 100 different Odyssey models. We took the same approach with Tiffany’s bases and metal parts, taking accurate measurements and making molds of everything that we thought might be useful to our restoration business. This acquisition process has continued right up to the present, so that by now we have a large notebook filled with Tiffany specs and many hundreds of different brassware patterns and molds at our disposal.

Paul Crist Studios and Odyssey Staff- 1989

● Even with Odyssey sales doing very well, Tiffany reproductions continued to make up the lion’s share of our business all through the 1980s. We maintained a staff of around shade 15 artisans to fabricate the shades, with another 6 or so working in patina, repairs and the various Odyssey functions. Our reputation for making the most artistic and accurate Tiffany reproductions was by now secure, but we still had to work hard to maintain our status in the field. Good glass remained the key ingredient to this preeminence. By now, Uroboros’ success with their lines of mottled. fractured and drapery glass, which I had had a hand in developing, was generating competition. Chicago Art Glass had come on the market with a line of very good Tiffany-like mottled glass in the late 1970s. Around the same time, Rod Craig, one of the original partners in Zephyr Glass, established a sheet glass business in Santa Cruz, CA, which he called Oceana Glass. After trying a line of more pedestrian opalescents, in 1983 Rod decided to concentrate on mottled glass and enlisted my help in achieving a pleasing mottled effect and in determining the color combinations that would be most useful to lamp makers.

The Tourist Makes Glass at Yough- ca 1987

Eric Lovell, Rod Craig, myself and John Triggs

Taiwan- 1989

● In 1985, I met John Triggs at a stained glass trade show in Chicago. Youghiogheny Glass had already come out with a good line of mottled glass in basic color combinations (the “high strike” or HS line), but John wanted to beef up this repertoire with glass that was more Tiffany-like. He solicited my help in developing this new line by making me an offer I couldn’t refuse. If I would come back to Connellsville and consult for several days, he would devote a couple of furnaces to experimental runs and I could take home a small part of what we ran. As things turned out, at the end of the day I was able to put together pretty much whatever color combinations struck my fancy and ship back home whatever looked usable. Needless to say, the best of what we ran was a lampmaker’s dream and the results were beneficial enough to both parties that we repeated the process at least a dozen times over the next decade. The fruits of this collaboration became Youghiogheny’s “RS” line. The experimental glass that was rolled out at the Yough factory during those weekend runs formed the backbone of all of the gorgeous shades that PCS was able to produce during the late ‘80s and all through the ‘90s. Over the course of this collaboration, John and I became good friends and, while my understanding of Tiffany’s glass informed him, his knowledge of glass chemistry and technology and, more importantly, his willingness to share that knowledge was crucial to my understanding of Tiffany’s glass production and its unique qualities. In the end, the knowledge that I learned from John has proven to be an invaluable tool in distinguishing between Tiffany’s Favrile glass and that of other makers, both contemporary and modern.

● The late 1980s and early 1990s saw a period of growth and consolidation for both Odyssey and Paul Crist Studios’ restoration business. During this time the fabrication of reproduction Tiffany shades remained an important part of our repertoire, but its primacy receded as the other facets of our business caught on and consumed more of our time. Notable projects during this period include:

□ Beginning in 1984, the engineering and fabrication of two Frank Lloyd Wright lamps for the Pentad Guild under license from Heinz & Co. Reproduction of these lamps from the Dana House in Springfield IL required extensive research, both to document the surviving lamps and to resource the materials used in fabricating them. This latter aspect required us to resurrect old technologies to make some of the parts, including reproduction of a key colonial came by Chicago Metallic and the fuming of several custom sheet glass colors by Oceana Glass. To date we have built more than thirty of these lamps, many of them going into important collections of Arts & Crafts furniture.

□ My knowledge of the art glass employed by Wright led to my being retained by the Dana House Restoration Committee, who were undertaking an extensive refurbishing of the house. My contribution was acknowledged at the official re-opening ceremonies in Springfield in September 1990. At that ceremony, Governor Tommy Thompson’s contribution was acknowledged by the gift of one of our reproduction lamps.

16" Fuchsia Lamp

designed for the Franklin Mint- 1986

□ In 1986, the design and prototyping of a 16” Fuchsia lamp for the Franklin Mint .

□ During this period, I gave more than 20 full-day seminar/slide shows on Tiffany’s lamps and the Odyssey system, including several overseas in Germany, Switzerland, Holland and Japan.

□ In 1988, the establishment of a separate woodshop to reproduce lighting by the Greene brothers and Gustav Stickley. We had been hired in 1987 to reproduce some of the stained glass windows for the Blacker House in Pasadena and, by extension, became interested in the exquisite fixtures in that house. After several trips to document all of the original fixtures in the house (which had been spread around the country), we enlisted the talents of master woodworker Flip Burton to reproduce the delicate and complicated wooden frames that the Greene brothers are famous for. Our work with Wright’s art glass made the job of duplicating the iridized glass that the Greenes had used relatively straightforward. Over the following years, we produced dozens of near perfect reproductions of Greene & Greene fixtures, again many of which went into major collections. We also made faithful reproductions of lamps by Gustav Stickley and Charles Limbert.

● By the dawn of the new millennium, our output of reproduction shades had been reduced to less than 20 a year, as Tiffany restoration was demanding more and more of our attention. Up until the last few years the greater part of this restoration was devoted to metalware, largely because the New York dealers were reluctant to send shades out to the West Coast for repair. Recently, this imbalance has begun to correct itself as knowledge of our resources and respect for our careful glass work has become more widely acknowledged. The recent acquisition of a large reserve of original Tiffany glass has helped a lot in this respect. Over the last few years we have been entrusted to do significant restoration on several important Tiffany pieces, the specifics of which must remain confidential.

Authenticating a Tiffany Lamp- 2011

● The last decade has also seem a dramatic increase in the demand for my services as an authenticator. This might be due simply to the questionable assumption that age brings wisdom, although I prefer to think that my long experience in hands-on restoration together with my understanding of the pequliarities of glass production have given me with a unique fact-driven perspective in evaluating and authenticating Tiffany lamps. This approach has proven particularly useful in conflict situations, where my opinions often carry more weight than those of other experts in the field, whose determinations are based largely on knowledge of stylistic features gleaned through exposure. Currently the Studio does an average of 5 or 6 authentications a month. Several of these have led to legal actions and I have given depositions and appeared in court as an expert witness many times.

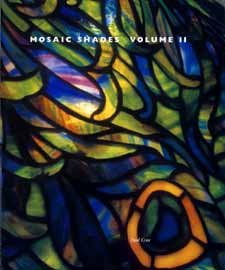

● In 1995 I became interested in the other companies that made leaded shades in the shadow of Tiffany. Exposure to several old non-Tiffany shades of exceptional artistry and craftsmanship piqued my interest in this largely unexplored field and I began what turned into a 10 year odyssey to learn what I could about them and to document their work. This research finally bore its first fruit in the form of my book Mosaic Shades II, which was published in 2006. The other two volumes of this series are currently in the works.