by Paul Crist

Edison "Bergmann" Socket, 1884 to 1895

SOCKET TUTORIAL

The years between 1895 to 1910 witnessed a rapid growth in the use of electric light and with it significant improvements in the design of light sockets. An understanding of what these changes were and when they occurred provides a valuable tool for dating early electric lamps. This discussion will gloss over internal modifications and focus on the external appearance, as this aspect is the most useful for on-the-spot assessments.

Although Edison invented the first functional electric light bulb in 1879, more than 20 years would pass before his revolutionary device was practical enough to be embraced by the mass consuming public. In fact, early electrical systems were exorbitantly expensive to install and to maintain, as well as subject to frustrating service interruptions and frightening power surges. As a consequence, the market for electric light during the 1880s was extremely small, and the number of “bulb receptacles” or sockets produced was miniscule. During this formative period, Edison's DC (direct current) system dominated the market and his "Bergmann" socket was the prototypical design.

Four Pre-1890 Thompson-Houston style Sockets

The first real challenge to Edison's hegemony came with the inauguration of Westinghouse's AC (alternating current) system in 1886. The Thompson-Houston Co., a supplier to Westinghouse, introduced the seminal socket for AC, which featured a distinctive cylindrical shell design. The T- H design was soon adopted by most of the other manufacturers, Edison being the noteworthy exception. This shell design was the standard until 1890, when Philip Lange patented an improvement that did away with the expensive solid brass cap of the earlier model. Lange's patent utilized a sheet metal cap with a small strap across the inside to anchor the 2 screws that held the socket shell together and the internal body in place. This 2-screw “strap” system of joining was cheaper to manufacture and gave the socket a more finished appearance. It was soon adopted by most suppliers and would remain a ubiquitous feature of mainstream socket architecture for the next 20 years.

Westinghouse

Thompson-Houston

Thompson-Houston

Edison

Four 1890s Lange style Sockets with the most common Bulb Bases

The Lange socket of the 1890s was basically cylindrical in shape with an angular cap whose lower edge covered the top of the socket tube. Switched models were equipped with a flat paddle that might or might not have the company's logo impressed in it. Because the electric market was still small, not a lot of these Lange sockets were made and they are somewhat of a rarity today. By the end of the decade, however, the use of electric light had grown to such an extent that the electrical companies were motivated to look for ways to reduce the cost of manufacturing sockets and improve their safety features. In 1892, General Electric took control of Edison's company and soon abandoned his DC dead end. In 1896 they introduced their first Edison screw base socket for AC use. The design, which was patented by J. C. Tournier, featured an improved switch design housed in a Lange shell. Tournier's switch was ingeniously simple, but it took up more space than the older Lange-type switches, necessitating an increase in the diameter of the upper half of the shell. The socket also featured a domical cap and a flat switch paddle with the GECo logo molded into it.

GE, 1896

Perkins

Bryant

GE

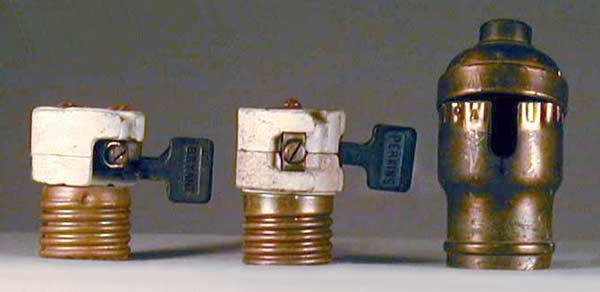

Three Tournier-type Sockets, 1900 to 1909

By around 1900, most of the other manufacturers, which numbered about 20 at this point, had adopted the new switch design and shell shape, bringing out their own versions with their name imprinted on the switch paddle. The main producers at this point were General Electric (GECo), Perkins, Paiste and Bryant (who had taken over Westinghouse’s socket production in 1890).

One frustrating aspect of the market during this period was the variety of electrical systems in use. All of the major electric companies had come up with their own complete system of components, which included proprietary methods of securing the light bulb in its socket. Of course, bulbs from one system would not fit the sockets of any other system and, while every company claimed their method was superior, their motive for exclusivity was arguably to keep their customers captive. By 1900 there were no less than 15 different bulb base/socket configurations on the market and this plethora of options was creating a nightmare for electric fixture manufacturers and merchandisers. That year the industry decided to settle on the Edison screw base as their standard and to gradually phase out the other systems. At this point Edison's base already controlled about 70% of the market, with 15% to Westinghouse, 10% to Thompson-Houston and 5% scattered among the rest. Sockets to fit the non-Edison systems continued to be manufactured for another 3 or 4 years, but by 1905 they had pretty much been obsoleted. We mention this bit of history because occasionally you will come upon sockets with these odd receptacles. As one might expect, they are quite common among the 1890s Lange-style sockets, but only rarely found on the later Tournier types. The Thompson-Houston version is the one most often encountered today because it could be fitted with a simple adaptor to accept an Edison bulb. This contributed to its survival, while all of the others eventually had to be replaced and were usually discarded as useless.

Edison

Westinghouse

Thompson-Houston

T-H to Edison Adaptor

The three most common Pre-1900 Bulb Bases

Like their predecessors, the earliest versions of the Tournier socket had no full insulating liner and relied on the two screws and a fiber sleeve around the front of the screw thread to separate the body from the shell and prevent electrical shorts. An alternative design replaced the fiber sleeve with a removable hard rubber collar that screwed onto the screw thread. Both of these styles lacked the circular mica insulator under the central contact. As early as 1899, however, concerns about electrical safety led the NBFU to recommend adding the mica disk and a full insulating liner to both the shell tube and cap, and over the next few years these measures were gradually phased in. At first the liners were made of a very hard fiber material (“elastoid” or "fibroid" ), but by 1905 they had pretty much been replaced by black paper liners.

GE Socket w/ Collar

Acorn Socket

Electrolier Socket

Porcelain Brass Candelabra Sockets

Other Socket Styles of the 1900-1910 Period

Small improvements to the Tournier configuration continued to be made all through the decade of the 1900s and there are many minor variations in shell shape and length. It should also be noted that, during this period, several other socket styles were also in general use—especially the keyless Acorn and Electrolier varieties. In 1901, the Perkins Co. was absorbed by Bryant, who continued to use the Perkins logo. Thus it is not uncommon to find a Perkins body in a Bryant Tournier shell and vice versa, and both seeming mismatches are legitimate. In 1907, Bryant changed the shape of both the Perkins and Bryant switch paddles to a straight rectangle, doing away with the arched top and curved lettering. (GE continued to use their curved version until about 1915.) Through the decade of the 1900s, the Lange 2-screw system of shell joinery remained the market standard, although it increasingly came to be perceived as both too expensive to manufacture and too troublesome to install. During this period, nearly every manufacturer experimented with some form of simpler snap-in joinery, typically involving 2 or 4 pins, slots and/or louvers. None of these attempts, however, worked very well and they were all fairly short-lived.

Bryant

Perkins

Louvered Shell w/ Bead

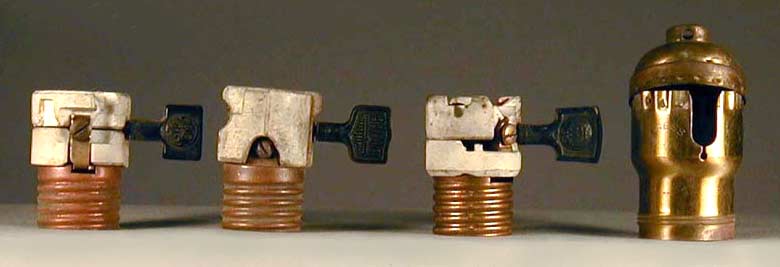

Early Louvered Paddle Sockets, 1909 to 1915

In 1908 Bryant finally solved the problem with an ingenious new method of “snapping” the socket shell together, which they dubbed the “New Wrinkle” concept. This new configuration featured a ring of 20 louvered slots around the top of the brass shell tube and a corresponding ring of perforations around the inside of the cap rim. This allowed the two parts to be securely joined by simply pushiing the tube into the cap and snapping it in place, a method that greatly facilitated the job of installing sockets inside husks. In addition, the 20 louvers permitted the socket tube to be locked in 20 different positions, eliminating the need to secure the cap at just the right angle so that the paddle would be pointing in the right direction. The earliest versions of the New Wrinkle socket left the rectangular slots around the rim of the cap exposed on the outside, but this was quickly deemed unsightly and within a year they added on a metal collar to hide the slots. The Bryant New Wrinkle or “louvered” socket shell design was so well received that by 1910 all of the major socket producers had obtained licenses to use the new technology. Many continued to offer their Lange-type sockets for a few more years, but by 1913 they had pretty much disappeared from the market.

General Electric

Bryant

Hubbell

UNO Shell w/ Exposed Louvers

Later Louvered Paddle Sockets, 1920 and after

The next significant change in socket design came around 1914 with the introduction of the UNO fitter. Prior to that time, all louvered sockets still followed the old Lange design of including a raised bead around the bottom of the tube to strengthen it. Shade fitters were added to the socket by means of a complicated little screw clamp that was mounted over this bead. In 1912, Bryant came up with the idea of replacing the bead on the socket tube with a ring of fine threads that would accept accept their new screw-on "UNO" shade fitter. From 1915 on, all of the other manufacturers adopted the UNO threaded tube and began to phase out their beaded version as redundant. By 1920 all the major producers had also replaced their block letter script on the paddle with a more decorative logo. Around 1930 they stopped covering the louver indentations on the cap and this “exposed-louver” look has been the standard ever since. The technical developments we have outlined so far apply to switchless sockets as well as to the rotary switch "paddle" types.

Pull chain sockets evolved from a totally separate source. The first pull-chain socket was introduced in 1896 by Harvey Hubbell, who was trying to address a serious shortcoming of the keyed socket. Keyed sockets often had to be installed in hidden locations (such as inside a dome shade), which made accessing the switch paddle difficult. Impatient consumers often wound up groping around inside the shade, a careless practice that could result in an electric shock. Hubbell’s first version utilized a standard Lange shell with an internal pulley switch operated by a silk “tuna line” pull cord. The tuna line protected the user from shocks, but it was found to wear out and break too easily, so Hubbell went back to the drawing board. In 1900 he patented an improved version (now with the wider Tournier-type shell) that accomplished the insulation internally and allowed him to use a stronger brass ball chain pull. Even though his improved socket was about 50% more expensive than the keyed alternatives, it became hugely popular and orders soon consumed his entire manufacturing operation. For 10 years the familiar “acorn” pull with its attached chain guide was a symbol of quality in lighting and most of the better manufacturers of leaded shades would install nothing else on thier lamps (Tiffany was the curious exception to this rule). Hubbell jealously guarded his patent and, for the first few years at least, granted no licenses. Around 1905 pull-chain sockets began to appear in the catalogs of other manufacturers- with Hubbell's acorn pull, but they were apparently not as well received since they are rarely seen today.

HUBBELL LANGE PULLCHAIN SOCKET

with integral chain guide, 1900 to 1910

TYPICAL LOUVERED PULLCHAIN SOCKET

with beaded shell and removable chain guide, 1909 to 1916

While the pull-chain socket was a big convenience for consumers, Hubbel's design represented a big headache for lighting manufacturers. The attached chain guide and the need to feed the chain through it during assembly made for a difficult and frustrating operation. In 1909, a few months after bringing out their New Wrinkle socket, Bryant came up with a way to attach the chain guide on Hubbell’s pull-chain socket to the ceramic body instead of to the shell. This neatly resolved the assembly problem and at the same time allowed the works to be housed in the same shell as their turn key version. The two companies may have traded rights to their patents, because around 1910 Hubbell also started offering the louvered shell. (They continued to also make their Tournier/Lange "classic" for several more years.) In the first Bryant pull-chain sockets, the chain guide was attached to the body with two small screws, but this was soon replaced by a simpler clip-in arrangement that featured two curved prongs on the detachable chain guide. This latter configuration was preferred by all of the other manufacturers, who added on their own distinctive pulls in the shape of balls, tassels, bells and the like. All subsequent changes to the pull-chain socket basically paralleled those to the turn-key style.

EDISON ATTACHMENT PLUGS

2 of many variations, 1880s to 1915

SPARTAN 2-PRONG PLUGS

Hard rubber, 1915 to 1930 Injected plastic, 1930 and after

The electric attachment plug was really a minor item in the years before the turn of the century. Up until around the time that Edison's screw base was accepted as the industry standard, there was very little need for plugs, because electric use was generally limited to hanging fixtures and sconces, which were "hard" wired and did not need to be plugged in. The arrival of the electric portable along with a plethora of home appliances after 1900 generated a need for a way to temporarily tap into the house current. The electric sockets in fixtures and sconces offered the only convenient access to power at the time, and the Edison Attachment Plug was enlisted to exploit this source. The familiar baseboard outlets and pronged plugs of today were actually around (in a somewhat different form) as early as 1902, but their use was hindered by the difficulty of installing outlets in existing residences . Hubbell introduced the first flat pronged plugs in 1904, but again, due to installation problems, there was not a big market for them. The Edison plug endured as the primary current tap until after about 1915, and as electrical conveniences proliferated, multi-outlet “plug clusters” and dangling electric cords became an increasingly familiar sight in American homes. The turning point seems to have come in 1915, when Bryant finally endorsed Hubbell’s parallel flat prong design and introduced it under the “Spartan” trade name. Thereafter, reliance on the Edison screw-in plug steadily declined, until by the mid-1920s it survived only in older un-modernized homes. The early Spartan-type plugs were molded in hard rubber, which makes them relatively heavy and dense. Around 1930, manufacturers switched over to injected plastic, which is thinner, lighter and retains a glossier surface. There were many styles of plugs made, but the dome-shaped varieties like those pictured above were the ones most commonly installed on portable electric lamps.